Deptford High Street • 27 March 1905

How one Deptford murder case made forensics history

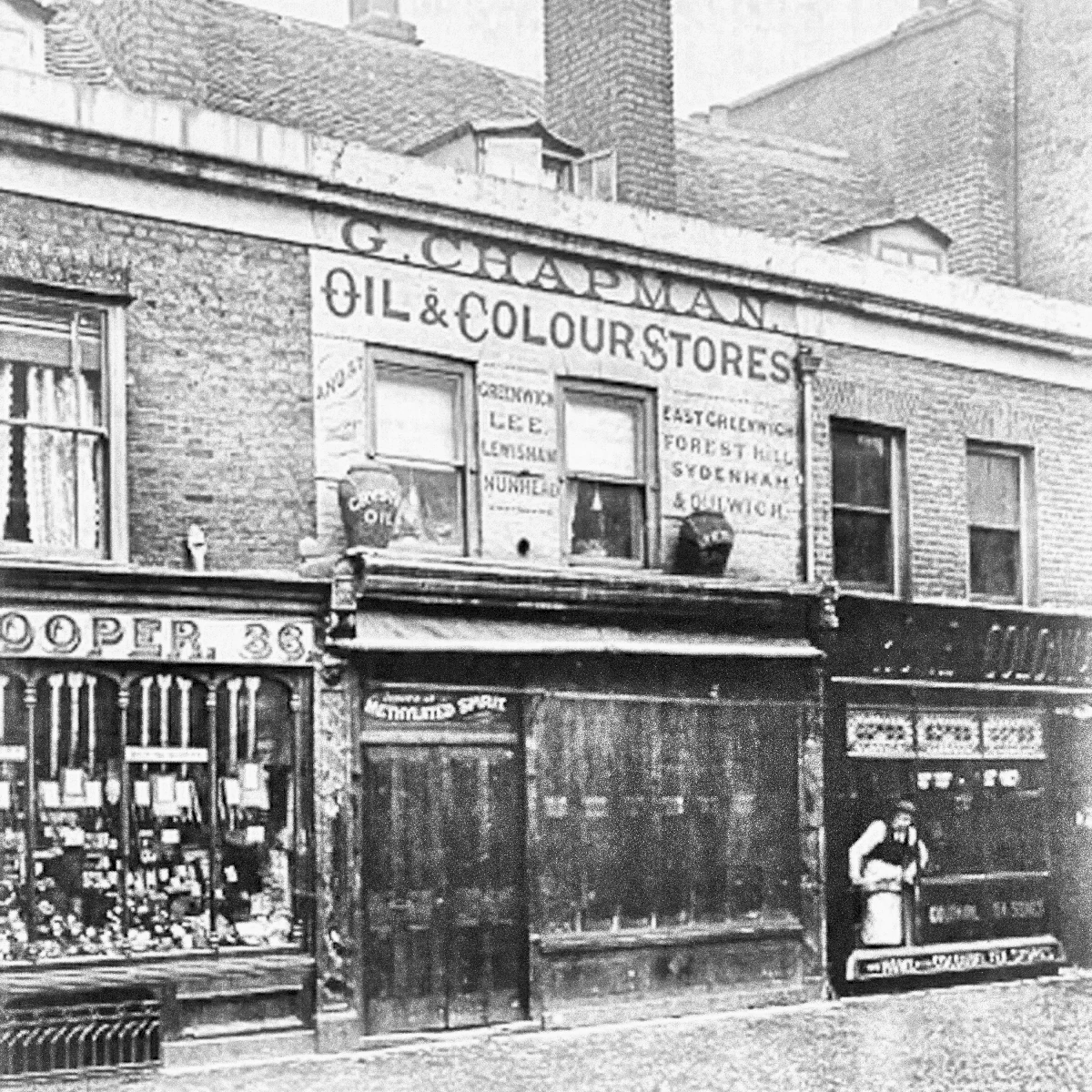

Dawn came quietly to Deptford High Street on 27 March 1905. One shop, though, stayed dark. Chapman’s Oil and Colour Store at number 34 should have been open, but its shutters were still down. When the assistant, William Jones, arrived, he found the door locked. He knocked. No reply. Looking through the window, he saw overturned chairs. Something was off.

William fetched help from a neighbouring shop. Together, the two men forced their way in. Inside, they found 71-year-old store manager Thomas Farrow lying dead on the floor, his skull smashed by heavy blows. Upstairs, his 65-year-old wife Anna Farrow was barely alive in bed, also suffering a fractured skull. She died days later without regaining consciousness.

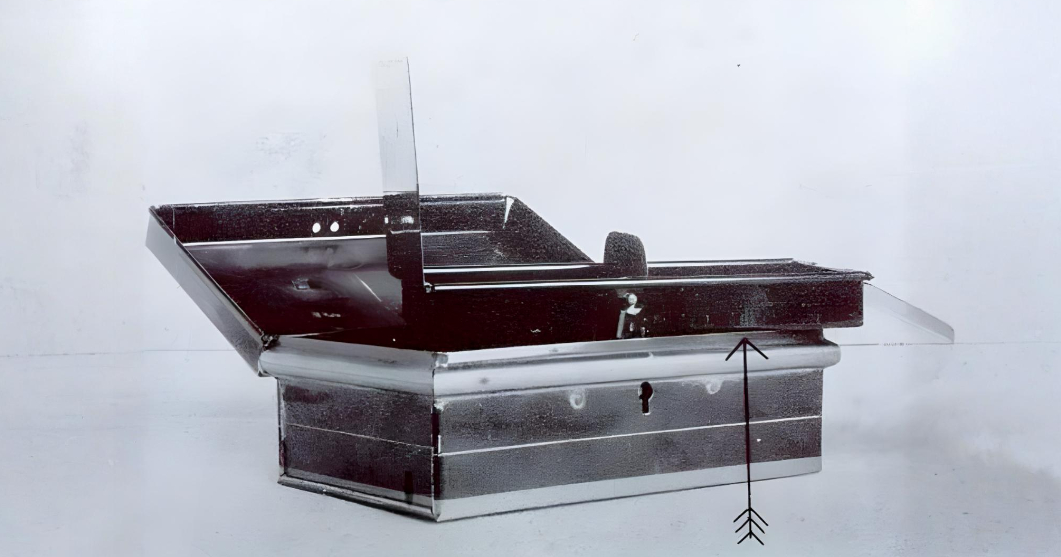

There was no forced entry, but the cash box lay empty. Two black masks, crudely fashioned from women’s stockings, had been discarded on the floor. It looked like an early-morning robbery that had spiralled into violence.

The investigation that followed gripped Deptford. Two elderly shopkeepers had been attacked in their own home, and no one had seen a thing. No clear suspect. No easy lead. Neighbours wanted answers. As police walked through the small rooms above the shop, they realised they were facing a puzzle that would not give itself up quickly.

One clue that changed everything

Local detectives examined the Farrows’ home and shop for any hint of what had happened. The couple were still in their nightclothes. Thomas had likely opened the door expecting an early customer and had been struck down. The attackers chased him into the shop and finished the job. One of them then ran upstairs, assaulted Anna, and grabbed the takings. The empty cash box lay beside her bed. According to the store assistant, about £13 had been taken — the shop’s weekly earnings.

The key question now: who were the masked men? With no eyewitness who could identify them, the case risked becoming just another unsolved killing in Edwardian London — until investigators noticed a greasy smudge on the cash box.

Chief Inspector Frederick Fox and Assistant Commissioner Melville MacNaghten, head of the Criminal Investigation Department, arrived from Scotland Yard. MacNaghten, who had helped establish the new Fingerprint Bureau in 1901, examined the smudge on the underside of the cash box’s inner tray. It looked very much like a fingerprint. It didn’t belong to Thomas or Anna, nor to the first officer on the scene. Which left only one possibility: the killer.

But in 1905, fingerprints weren’t routinely taken from the public. Unless the attacker was already on file, the clue was little help. Collins went through all 80,000 prints one by one. No match. Halfway through, he had caught himself imagining some future device that might search them in seconds.

So the police returned to the streets of Deptford.

The first fingerprint conviction

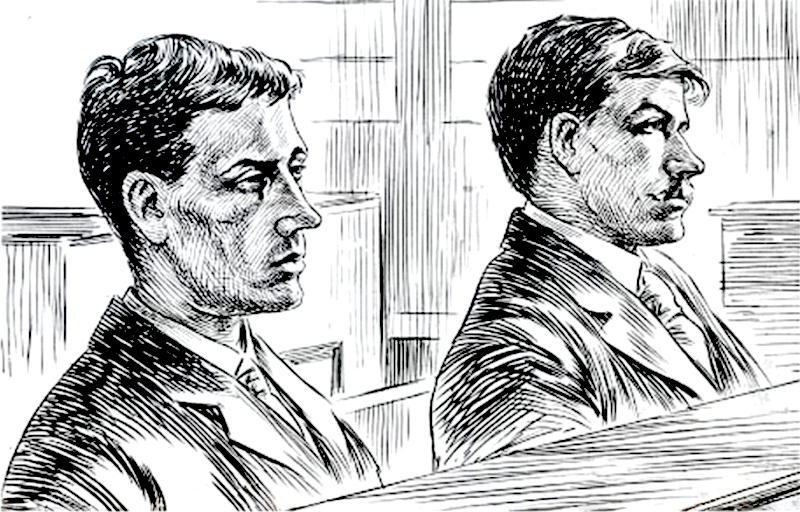

The case that supposedly had no witnesses suddenly produced some. Two locals remembered seeing two men slip out of the shop at 7.15 a.m. One was identified as 22-year-old Alfred Stratton, known for petty violence. The other matched his younger brother, Albert, aged 20.

T hey had no prior record, but Alfred’s girlfriend, Annie Cromarty, said he’d behaved strangely: asked her for old stockings the night before, returned home smelling strongly of paraffin, likely used to scrub away blood, and made a burst of spending that didn’t match his usual finances. She also told police where the rest had gone. £4 was recovered, buried near the waterworks on the Ravensbourne. The case was tightening.

Police arrested Alfred at the King of Prussia pub on 2 April; ; Albert was caught the next day on Deptford High Street. They were charged at Old Greenwich Police Station on Blackheath Road. Once their fingerprints were taken, the investigation finally had a breakthrough. Collins compared Alfred’s right thumb to the print on the cash box. It matched perfectly.

At trial, the prosecution leaned heavily on fingerprint science. Collins explained that no two prints were alike and that Scotland Yard had never found a duplicate among hundreds of thousands. He showed photographs of the ridge patterns on the cash box and Alfred Stratton’s thumb. They lined up point for point.

Fingerprint evidence had solved burglaries before, and it had appeared in murder cases abroad — in Argentina in 1892 and in India in 1894 — but it remained a novelty. In Britain, no one had dared test it in a high-profile trial. Not until Deptford.

It gave the defence an opening. Their expert, Dr John Garson — the man who taught policemen how to use fingerprints in the first place — now claimed the whole technique was too new to trust. Under cross-examination, though, he admitted he had offered his expertise to both sides before even seeing the print. Garson had effectively declared himself available to whoever paid quickest. A judge later called him an “unreliable witness”, which was a polite way of saying he’d turned the trial into a job interview.

The jury did not take long. After under two hours of discussion, they found Alfred and Albert Stratton guilty. On 23 May 1905, the brothers were hanged at Wandsworth Prison, the first people in Britain condemned with the help of a fingerprint.

From that point, detectives knew they were no longer alone with their hunches. Surfaces, objects, and traces could now speak for themselves. In a small shop on Deptford High Street, a single thumbprint showed what forensic science would become.

3 December 2025

References

- Fingerprints: The Origins of Crime Detection and the Murder Case That Launched Forensic Science. Colin Beavan

- Murder Houses of South London. Jan Bondeson

- The Crime Book. Shanna Hogan et al.

- Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living or Dead. Harris Hawthorne Wilder & Bert Wentworth

- The Stratton Brothers: The UK’s First Murder Case Solved by a Fingerprint. Richard Clark

- Fingerprint Saw Brothers Hanged for Brutal Murders. Jan Bondeson

- How the Stratton Brothers Became the First British Killers Busted by a Fingerprint. Robert Walsh

- Stratton Brothers. Murder of the Farrows: Daily Mirror Reports 1905. Old Deptford History

- ‘Mask Murder’ Brothers Hanged for Slaughter of Pensioners During a Botched Robbery — First Convicted of Murder Using Fingerprint Evidence. Steve Myall

- In 1905, Fingerprints Pointed to Murder for the First Time in London. Jennifer M Wood

- Deptford 1905. Caroline Derry

- Farrow Murders: The 1905 Deptford Case That Sparked a Fingerprint Revolution. George Pallas

- Fingerprints: The First ID. Melissa Bender

- 2nd May 1905: Alfred Stratton and Albert Stratton. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey